- Home

- MADHAV MATHUR

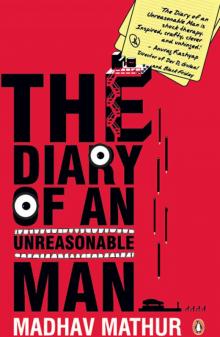

THE DIARY OF AN UNREASONABLE MAN Page 2

THE DIARY OF AN UNREASONABLE MAN Read online

Page 2

There had been some appreciation for our work in the recent past, by those who understood it in its entirety. The rest, we were still trying to reach out to. We made the news a lot, but of course, only as the Anarchists of Mumbai.

2. THE BEGINNING

My life had become a long, arduous practical joke.

An alarm went off. It was the usual annoying-by-design beep on repeat. After a while, it sounded like the latter half of Tool’s epic ‘Eulogy’. It had the ominous overtone of Bach’s organs. It had the intensity of a witch’s nine-inch-long nails scraping the surface of a grim blackboard, with the promise of pain. It rang in my apartment on my bedside table. The radio switched on automatically too. Yuppie-friendly gadgetry to get your ass on its way to more cheese, in style. I rubbed my face, seriously contemplating the necessity of what I was about to do, again.

We had an old-looking apartment, decrepit and minimalist. A slightly scuffed sofa, a sturdy table with a couple of chairs, an old television, that was our drawing room. It was clean and quiet, ready for parental inspection in less than five minutes. This was supposed to be our temporary place before we adopted the joyous condo life of the undeservingly-rich-and-dying-to-be-famous. The morning light fell on our pale yellow walls and the ill-shaped drawing room spotlight grew.

I could smell the morning rain. Another muggy June day pushing me to stay in bed, inactive, incapacitated.

But alas, ‘condominium coolness’, wealth and joy come not easily to the lazy. I reached for the clock and slammed the damn thing down hard, staring into my empty balcony. My dying plant, a crow on the electricity lines criss-crossing the sky, a view of the building across the road–sights seen every day, like clockwork, like the insides of a machine. The plant had been a gift from my sarcastic friend Shahnaz. She told me I ‘needed some green in my life’. Look at it now. Yellow and dry. Even the birds in our neighbourhood seemed to work on schedules and appointments. Who could blame the poor things? Routine ruled us all. Well, most of us.

Lying on the dishevelled bed with crumpled sheets and pillows strewn all over the place, evidence of another night spent tossing and turning, I traced the slowly moving blades of the fan. I suppose after you’ve been beaten into a mould long enough, you start asking whether you deserve any better. I was close to entering into my own sickly comfort zone, loathing myself for sometimes believing that what I had might just be it. I felt like a horrible tool. Dreams of achievement, dreams of changing all that’s wrong had been replaced by drab Excel spreadsheets with macros to boot. My personal island of torture. How could I possibly spend more years like this and ‘grow within the business’ to be a clown like my boss? Selling bullshit for top dollar and smiling through the ignominy of being a hopeless sell-out myself. How could that make anyone feel even remotely content? I rubbed my eyes to fully wake up.

‘Live better,’ signed-off the annoying bubblegum announcer on my radio. I kicked it to a stop and punched in some Queens of the Stone Age. A lot of the time music provided me with an escape. It was my numbing agent, delivering peace, shifting focus: anaesthesia for the day’s surgical assault on my self-esteem and soul.

‘I am not condemned … no this is not a chore … I am not condemned …’

Musically inspired auto suggestions for peace and calm too proved to be just temporary. The walk to the bathroom was slow and pronounced. The music was loud. Josh Homme insisted that I had a ‘Monster in my Parasol’. I wish the song was about that. My monster was in my head. I decided to smoke it out. Not by means of a massive self-immolation bid, of course. I merely popped in my morning ciggy.

I wondered about the millions of pathetic clowns in a million houses getting ready just as I was. Digging through a lame wardrobe of weather-beaten white shirts, grey and black pants, yellow ties, smoking that first morning cigarette to get the day started. I saw the same sorry sight again.

I finished with my ablutions and made my way to the front door through the common area, fixing my tie knot. Ties were a must for days that we met clients.

Abhay, my housemate, had already picked up the papers delivered to our doorstep.

‘Oye, have you seen my paper?’

‘One sec, sorry da, picked up yours with mine.’

Abhay had a distinct liking for Today’s News. I liked News Today. We sat at the table reading with a cup of tea and some lightly buttered toast. I continued my bid to delay myself, buttering and rebuttering my toast till Abhay snapped at me. ‘Want me to inject it directly into your arteries?’ he asked. I stared at him and dead panned, ‘I need the lubrication.’

Abhay was the kind of guy who could be happy pretty much anywhere. He had given up any aspirations he might have had of being a world-beating reformer, his idealism had transformed into a dull daily ache that he was learning to ignore. We had studied together in college. We had been room-mates for two years there. He was a good guy, an ideal son and a reliable friend who had always tried his best to keep me out of trouble. He was my lanky Tamilian housemate in search of his mother’s daughter-in-law.

I didn’t want to be where he was though, in that state of acceptance. I still saw plenty that was wrong. I still felt the need to hit out at the powers that be, which had put me where I was. The well-oiled machine that had fooled me into ‘gaining’ all that I had.

In any case, he was a fairly successful chemical engineer. He knew his job and did it reasonably well. I had made a switch. I got bored of the engineering curriculum and took up an advertising and marketing job with a renowned firm.

Trouble is the conformist coward in me. Twenty years of doing ‘the right thing’, doing ‘well’, building my life, getting that condo, getting that car, pleasing my parents and my loved ones, that was the sum of my life. Responsibility to one’s immediate family and managing their expectations has always been a priority. It is so for a lot of us and clearly this is where I get defensive.

Even the great Houdini would have had a hard time pleasing audiences today. Everyone’s an escape artist, building illusions for themselves, building alternative realities where they’re heroes. Distributing opportunities becomes a euphemism for keeping poor people in debt by lending them some more. Garnishing the details becomes a delicate way of saying ‘we’re going to lie our asses off and smile’. It could wring your neck or pound on your soul. It could gnaw at your insides, like a million murderous maggots were being poured into your bloodstream for a delightful serving at an abominable feast.

You’re it, though. You’re the hapless serving hurriedly venturing out of your apartment at 7.35 a.m. to reach your fantabulous office by 8.29 a.m. I turned to Abhay and said in my fakest television presenter voice, ‘Have a great day at work!’ He laughed sardonically and with a smile on his face, pointing with his right hand, said, ‘You too!’ For a moment we were easily excitable pre-pubescent VJs from the ‘music’ channels.

I followed him out of the apartment and down the stairs. We stood on the pavement in front of our building. I was imagining the tedious walk ahead. The rain had stopped and minor puddles marked the street. I pulled out my pack of cigarettes despondently. It was like our own little Matrix moment that has been overplayed and poorly replicated by numerous artists after the original. It’s a telling instant when everything ceases, does a neat 360 and you grit your teeth at the end of it, because nothing has changed. The emptiness still looms large, the dung by your feet is still there, and you’re still slowly poisoning your lungs. You’re just a little more aware of everything. There’s no leather-clad deep kick flying outwards. Not yet. Not quite yet.

I walked towards my office. The feeble walls on the side of the pavement had cracks in them. I could see faces in each of them, bricks with character grudgingly holding up structures that were housing the quiescent. People walked by me, faceless people with a purpose. Don’t get me wrong; I judge us not for what we do for a living. I judge us for our state of oblivion, people expecting and accepting lies and bullshit. It’s heartbreaking. This is not what w

e were meant to be. We’re capable of so much more. I believe that. I know that.

The fruit seller on the roadside sat looking at his diseased wares. I guess the rain and poor shipping had damaged some of them. He stared unseeingly at the grapes and oranges before him willing them, I think, to become fresh and whole. Seeing a large crowd approaching he suddenly came alive. He began a long rant about his fruits. Short of grabbing people and force-feeding them the fruit, he did everything he could to fill polythene packets with parts of the pyramids before him and palm them off.

The moment you look at an ordinary fruit seller in the middle of the road and think of him as a metaphor for what you’re getting in life, you know you have to do something about it.

I walked on.

It wasn’t that I didn’t express my anger, my thoughts on what was wrong. Abhay and I discussed politics, ethics and what we’re here to do all the time. Our levels of desperation used to range from ‘Somebody’s got to beat the shit out of that guy for anyone to learn anything’ to ‘I wish I was there, making policy, shaping opinions’.

Sure we’d seen the movies where some fresh-faced kid takes things into his own hands, destroys the evil political party, gets the girl, beats up gangs of miscreants and kills Amrish Puri. Sometimes we were quite convinced that Sunny Deol should really do that shit. At others we realized that it would never work and that violence was not the way to fix things. Violence loses you the all-important moral high ground. It fucks your credibility and leaves you in the ranks of common criminals.

Then there were the non-violent protests, candlelight vigils and marches. Good ways forward, but far too common and far too tame to have any impact on anyone for an extended period of time. We’re all too jaded to be moved by a mass of people shouting slogans or lighting candles.

Sure we could start NGOs and work at the grass roots, without asking too many questions and encountering the establishment only when it was damn near necessary. That sounded good. That sounded appealing. But hell, to reach out to over a billion people and to reach out to them fast you had to make a statement. You had to capture their attention and their imagination. How the fuck does one do all that? That was the question that dogged me.

So, all my tirades and anxieties found their way into my essays. They weren’t just scholastic ponderings of an angry kid. They were action statements with detailed descriptions of how to mess with whom. They were my voice. They gave me an outlet, and embodied my venom and pain. It was only a matter of time until the right stimulus came along: the thing that would push me over the proverbial edge, leading me into an abyss of my own creation, a dark tunnel with a 3W bulb flickering at the end. I didn’t care. I’d choose a dying bulb over a blazing exit sign any day.

Sense by sense, I assimilated everything on my way again. I could see a potpourri of colours, the distinct stench of fresh sewage assaulted my nose and I heard the crass cacophony of a hoarse man screaming at another. They seemed to be colleagues. Perhaps accomplices would be a better word, given the nature of their conversation. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I stood rapt in amazement, stunned by the unfolding conversation in the car idling at the traffic crossing.

‘Why the fuck did you have to shoot him after I did?’ barked the bigger man in the driver’s seat. He was gritting his teeth and beating the steering wheel as he spoke. The other fellow sat guiltily beside him, looking down.

‘He would have …’ he whined.

‘Did he?’ It was a terrible inquest. Each question made the little man on the side shrink deeper into his seat. Passers-by could see that something was wrong between them but most just continued on their way. I was, for some reason, rooted to the ground.

‘He could have …’

‘Skill-less, loud-mouthed asshole!’

‘He was shaking like an auto, I thought he was going for his gun …’

‘That’s what always happens! You didn’t have to shoot him in the head after that! How many times have I finished the job with a clean shot to the chest? How many times has anyone recovered from that?’

‘Never …’ came the uncomfortable reply.

‘Ended up mopping the bloody place. Do I look like a fucking janitor to you?’

‘I’ve never seen so much blood in my life either, I think for fat guys we should limit the bullets to a maximum of one …’

‘Don’t change the fucking subject … Today you messed up …’

All this while I stood by their rusting Fiat, not realizing that the light had changed and I could cross the road. Then the big guy stuck his head out of the window and started announcing to people in the street, ‘Meet Anand Sarkar, everybody! The man who shoots the dead, ruins the living and is slowly putting Yamaraj out of business.’

‘Basuji please, what is wrong with you? Please, please stop …’ squealed the sidekick.

‘He’s the best in a long time, his aim would put the great Arjuna to shame, his resolve would make even Bhishma Pitamah weak …’ Basu continued undeterred by Sarkar’s yelps of indignation.

‘I beg you, please stop … I won’t do it ever again, Basuji!’ Sarkar wheedled.

The pleading worked. Basu wriggled his torso back into the car.

‘If you ever give me shit about how you’re a slayer and this is what you’re meant to do with your life, I will personally kick your sorry ass all the way back to Dhanbad, you fucking idiot!’

‘I said … I know nothing else …’

‘You know nothing. My hands are still stinking.’

Their argument continued. They must have done some other sucker in earlier. How could these guys be so unaffected by that? Sure, they were ‘hard’ hit men. Even I could see that. Raised on the street, shoplifted as kids, been beaten up and then beaten up people. Sure. And here I was uncomfortable with what I have to do for a living.

What about prostitutes? How do they convince themselves to do what they do? Times of difficulty drive us all to do things we don’t want to.

Why should being a prostitute even be an option?

Why should being a hit man even be an option?

Why should being a marketing hotshot even be an option?

My ponderings about diverse and possibly reprehensible jobs were interrupted by the quick and loud snapping of two dirty red fingers.

‘What the fuck are you looking at?’ It was the big guy from the car, Basu.

I had a bad habit of sometimes getting lost in my thoughts and forgetting where I was, or what I was doing. As a child I had stood in corners for it, done the murgi. My most recent suspended animation moment had led to a long lecture from an irate female driver, about the importance of ‘seeing where you are going’ when you’re in the street. Until then it had been a source of amusement. Never thought it would almost get me killed.

‘What the fuck are you standing here and listening to?’

‘He probably heard everything, Basuji …’

‘Come here!’ said Basu with a sense of ownership that I resented.

‘Come here, you prick,’ Sarkar, the ineffective sidekick reiterated, as if I hadn’t heard his boss.

I didn’t fear them. I knew that if shit happened, the nearest policeman was about a hundred metres away. I also knew that he weighed about a hundred kilos.

I walked to the side of the car with caution.

‘What did you hear?’

‘Nothing.’

‘What were you looking at?’

‘Nothing.’ I replied with a half shrug.

He smirked and asked me coyly. ‘Do I look like a bad man to you?’

‘No, you look just fine.’

‘That’s right. He’s your regular, honest to God, bona fide living saint: Basuji.’

‘Why the fuck are you giving him names, Anand Sarkar from Dhanbad?’ he retorted menacingly. The sidekick realized he could do nothing right that day and apologetically fell silent.

‘I believe you,’ I reassured them.

‘You don’t think otherwise,

do you, tie-shirt?’

‘No. No, I don’t.’

‘Saala Phattu!’

‘He’s just another insignificant tie-shirt … forget him Basuji.’

‘Get the fuck out of my sight. If I see you looking our way again, I’ll plug you right here.’

I backed away, chagrined and angry, primarily because the rabid and uncouth murderer was right. He had read me for what I was and written me off with even greater ease. I was a nothing. I was a glorious, meaningless observer incapable of doing anything to him.

I stared down at the asphalt. Should I step out, out of turn? Should I complete my ineptitude and end my misery with a generous dose of bus engine bustle in my face? No. I will bring their war to them. Some day I will.

The light changed.

Taunting cries of ‘Bye tie-shirt!’ were the last I heard from Basu and Sarkar, as the squabbling dynamic duo blew kisses at me and drove off. Should make a note of their names.

So it ended; my perfect morning walk that is. Leading me gently into my office, an awesome place where grand deals were struck between hawkish bigwigs; where superb minds were put to their best use, coming up with magnificent ideas to sell cold drinks and chocolates. I was ‘home’.

I walked past my boss’s office, with its ostentatious wall hangings dominated by a framed print of a Dali that he routinely referred to as a Vinci. Fucking yuppie jackass. Could be me in ten years, if I do nothing about my life actually. He was a nice guy at heart I suppose, just a tool of our times. Forcing numbers down our throats, re-enforcing deadlines and restating the obvious, interspersed by pep talks that belong only on syrupy Zee TV kids’ shows of old.

‘You belong!’

‘There is something special about every one of you.’

‘Tap into your potential.’

Well, I’m all tapped out, sir. And no, don’t ask me for the Pegasus shorts.

‘Pranav, where are the Pegasus shorts?’ I heard him boom from behind me.

THE DIARY OF AN UNREASONABLE MAN

THE DIARY OF AN UNREASONABLE MAN